Principles of Design.

Order versus Nature

While getting good at landscape design is hard, there are some basic principles that will help you fumble your way to a great yard.

The Bible says that God made us in his image. Dorothy Sayers comments that one way we are in his image is our urge to create, to make. In any project more complicated than a toothpick the creation process involves trade-offs and balance between conflicting desires.

At one level our landscapes are attempts to impose order. We get the illussion of control, and by thinking that we control it, we feel that we own it. (My biases are showing...) At another level we are trying to imitate nature, usually with limited success.

As with many things, we must seek balance. To me the most interesting yards are ones with areas of order (mown grass, neat flowerbeds) with areas close to natural. (patches of wild strawberries, groves of poplar, plots sown with mixed seeds.)

Patterns

We like patterns. But too much pattern is boring. So we make patterns of patterns. We can nest this arbitrarily deep. Example.

Repetition as a design element.

If one is good, we repeat it. Repetition makes it look planned, orderly.

Alternation as a design element.

That's a little more interesting, but still boring.

Patterns of patterns. Note here that we’ve introducted a space as an element.

Now it gets interesting. This amounts to A B A C A B A D ... There's a pattern there, but there is also an non-constant part. The ABA part is like the base chords in a song. The CDCE is ambiguous. Will that part continue as CDCECFCG.. or will it continue as CDCECDCFCDCECD...

Here's a few more:

Alternating tall and short.

Tall row in the back, short row in the front. When you use two rows, you don't have to have the same spacing in each row.

At some point the brain gives up looking for patterns, and all you see is 'plants' For most people a pattern that is just out of their grasp is nice. They can tell there's pattern, but it's not obvious exactly what it is.

Oh, if you try complicated patterns, do it initially with bedding plants. Your experiments are a lot cheaper, and a lot faster. Which may mean you don't buy trees from me this year.

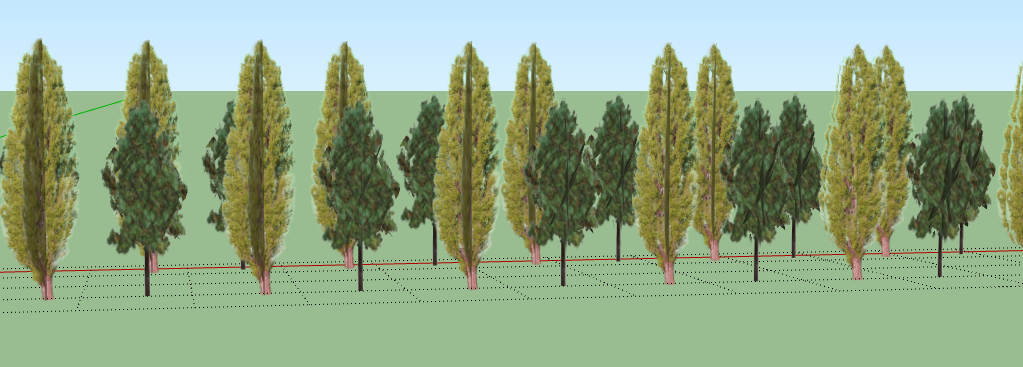

This is an good example of alternation used for a windbreak. Spruce stay wide at the bottom. Poplar drop their lower branches as they get older.

It's useful in another way too: You can plant a short lived fast growing tree, and a shade tolerant slower growing tree. By the the slow tree gets big, the fast tree will be ready to become firewood. You can use poplar to shelter maple and oak spruce and fir this way.

Poplar and spruce work well this way. Pine and spruce work too. Poplar and pine aren't as good -- the poplar make too much shade for the pine to do well.

Basic principles.

Ok, you saw me playing above. Let's talk about some of the principles.

Repetition.

This is simply putting another one down beside the first. If one tree looks good, two will look better. This is the easiest principle.

Alternation

If I alternate lilac, dogwood, lilac, dogwood down the driveway, I create repetition at two levels. My shrubs are still spaced 5 feet apart, so the concept of shrub space shrub space alternates every 5 feet. But because I use two different shrubs, there is an repetition happening every 10 feet too.

Contrast

When you put two different things next to eachother two things happen: The first is that the dissimilar attributes are magnified. The second is that the differences between two repetitions of the same tree are diminished.

Example. I planted a row of Scots pines. Some are now 8 feet tall. Some are only 4. I notice the discrepancy in height. Suppose however I plant a diablo ninebark between each one. Ninebark is a 4-6 foot shrub fully grown, but it looks very very different from the Scots pine. Because of the ninebark in between, the differences between a short pine and a taller pine are less noticeable.

The contrast can be in different forms: Colour, shape, texture, height. You can change one but not change the other. E.g. Blue spruce and white spruce both look like spruce. But the white grows twice as fast, and is usually darker in colour. So a row of alternating white and blue spruce will look like a picket fence for a long time.

Space

Space is an element. Good design uses space, not just as a place to put things, but as a frame, a separator. Space itself can have a shape. The effective use of spaces gives depth to a view. Look at a photo of the Grand Canyon. The number of different levels of detail make the space itself look huge. You're impressed not by a stack of flat rocks, but by the space that contains/is contained by the canyon.

Edges

Edges add structure to a view. As a species edges have been important to us, marking differences. Many animals prefer to live at the edge, or on the boundary. Look at the variety in the squelchy bits at the edge of a pond, the tide water zone at the ocean, the number of birds that nest in trees but forage on the prairie.

Symmetry

Symmetry is a type of repetition. It's regular repetition around a line or point. When you put one columnar juniper on either side of the front porch, that's symmetry. When you have a square flower bed with red petunias in all 4 corners, surrounded by lobelia, that's symmetry. In the first case it's symmetry around a line -- mirror or folding symmetry. In the second case it's rotational symmetry, around the centre.

Highly symmetrical yards look more formal, less casual.

Broken Symmetry.

Do something to establish a pattern, then twist it in some subtle way. In music you would call this 'variations on a theme' You're repeating something you did before, but with changes. There's still enough similarity that you have continuity of pattern, and this makes it look deliberate, but there is enough different to make it fresh.

Example: In that 4 sided planter, put white petunias in one corner. This breaks the 4 way symmetry, but leaves mirror symmetry along the diagonal that has the white petunias.

Example: I have a pair of Rocky Mountain Juniper bracketing the driveway at the curve. The shrubs on both sides of the road go:

Bog rosemary -- Darts Gold ninebark -- Diablo Ninebark -- Darts Gold -- Diablo -- Juniper -- Purpletwig dogwood -- Sea buckthorn -- Purpletwig -- Buckthorn -- Rosemary.

Look at the patterns: 1, 2 repetitions of 2, 1, 2 reps of 2, 1 But look at the colour pattern: Purple repeats every other shrub, once started. And in height we go low middle high middle low. This is a multilevel pattern that appeals to me. Mind you it’s right at the edge of pattern recongnition. Most people will see the ramp up/ramp down in height, and that the right and left sides are the same, and not notice the rest.

Proportion.

Certain ratios are pleasing. The golden ratio, about 1.6 to 1 or, if you prefer whole numbers, 8:5 comes up over and over both in the natural world and our own creations. Most cameras take pictures that are close to this ratio. Square flags are uncommon. So are ones that are twice as long as they are wide. Most of the rooms in our houses, other than the bedroom are close to this ratio. A room that is twice as long as it is wide, is hard to use. Most of the time you will end up dividing it either with a wall, or by how you arrange the furniture

Shape

Certain shapes work well. Circles. Squares. 8:5 rectangles. Most things between 2:1 and 5:1 are awkward. Longer than that, it becomes an edge, rather than an area. This one reason why the space between the front walk and the house foundation is seldom larger than 5 feet. In a house a room that is more than twice as long as it is wide is hard to use. In big houses, you end up putting several conversation centres in it to break the awkward shape into smaller zones.

Curvy, round shapes tend not to mix well with boxy shapes, unless they

are of different types. E.g. You can have square planters scattered

along a curvy path. But straight paths with right angles don't mix well

with curvy paths. This is one of the less rigorous principles.

If you break it, however, step back, and make sure that there are enough

unifying things to hold it together.

Hidden vistas.

A yard where you can see everything is boring. There's no surprise; no feeling of "What's around the corner?" If you have an acreage, you have room to play a bit. You can create lines, and rows, and groves of trees. But even a small yard needs a tree, so that you can't see all the house at once. This need to see what's behind the tree is hard-wired into our genes. The colleagues of our ancestors who didn't pay attention to what was around the next corner got eaten by the tiger who was waiting behind the tree.

Mass balance

This is a subtle form of symmetry. You don't have the same thing, or even the same shape, but you have the same amount. E.g. a single tall narrow juniper and a wide spreading juniper -- they both take up the same amount of space on the back of your eyeball when you are looking at them.

Non-random random.

Look at the following patterns:

This particular one at first looks like you just flipped a coin. But there is never more than two of the same in a row.

Another example.

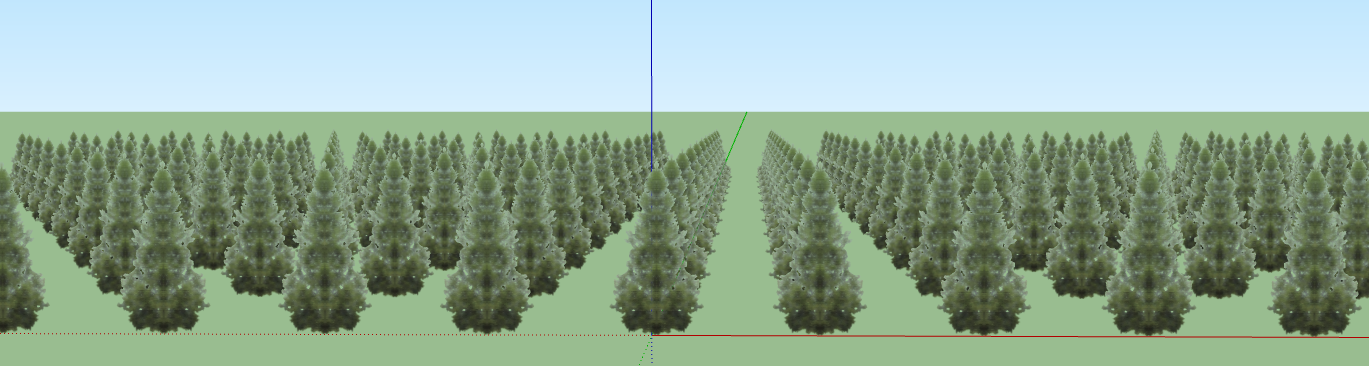

If I plant in straight rows, it looks like an orchard.

Boring.

But suppose I take out about half the trees at random, but leave them on their grid

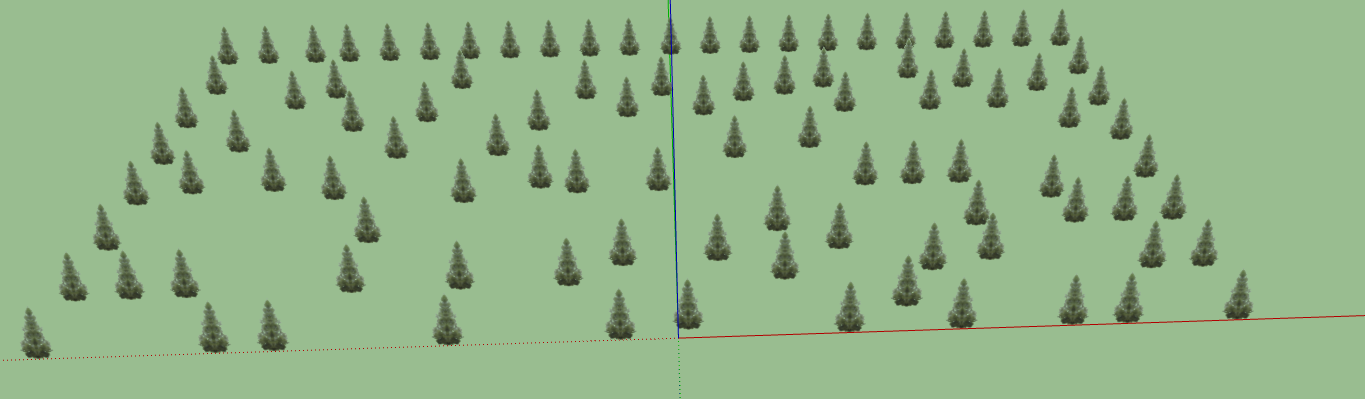

In this next two views, I've moved about half of them.

Note that throughout I'm leaving the back and side edges as regular spaced rows.

The trees have grown some now, enough that one of those other aspects is coming into play: hidden spaces. There are bits where you can see an opening leading off, and you wonder, "What's back there." (Ok, you're really wondering if you left room to get through there with the mower...)

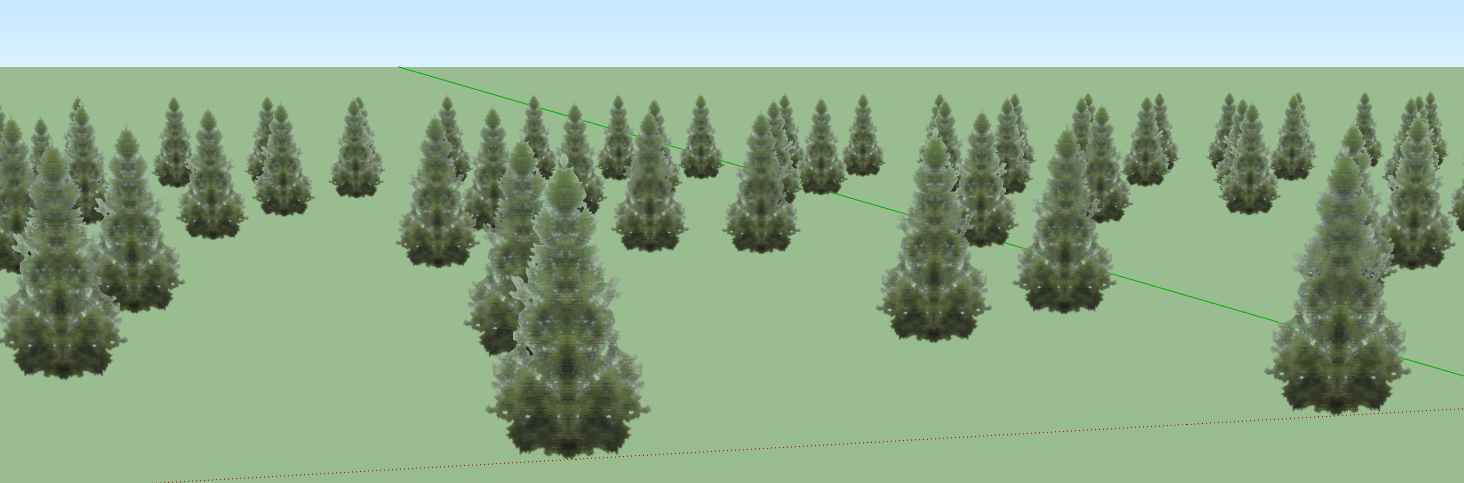

Now take that a step further, and tighten up the spacing a bit, and then remove 1/3 of the trees at random.

In this case we have done a forest of a single type. No reason to. Bear in mind the tolerances of each tree. Poplar are fast growing sun lovers. Put them anywhere. Pine are about half the speed of poplar but still need sun. So try to keep 30-40 feet south of a pine free of poplar. That way it will get the midday sun. Or put them on the edges. Spruce are about half the speed of pine, but they are shade tolerant. Maple and oak and fir are also shade tolerant.

A good way to start is to sketch a map of your yard at a scale of 1 poker chip = 12 feet. On this scale a loonie is about 8 feet, a quarter about 6 feet, and a dime about 2 feet. The poker chips are the diameter of a middle aged spruce. On this scale the spruces will grow together if the poker chips touch. By the time they do, however, they will be tall enough that if you need to go between them you can do some judicious pruning without destroying their appearance.

Start off by placing white poker chips with a dime's space between them in an array. Roll a pair of dice for each chip. If it comes up 1-5 remove the chip. If it comes up 8 or 9 replace the chip with a blue one. If it comes up with a 11 or 12 replace it with a red one.

Now take a look. Each colour of chip represents a type of tree for your forest. So white could be spruce; red, pine; and blue Manitoba maple. In some cases you don't have a clear path. Don't be a slave to the dice. Move a tree er... chip out of the way.

This is a non-trivial way to plan your yard. You can spend many evenings with your map on the dining room table. (Take pictures of it now and then so you don't lose it all when the cat decides that a table in the sun was meant for a nap.)

Then, there is the...

No, not tonight. That's a whole new topic.

Got something to say? Email me: sfinfo@sherwoods-forests.com

Interesting? Share this page.

Want to talk right now? Call me: (8 am to 8 pm only, please) 1-780-848-2548

Do not arrive unannounced. Phone for an appointment. Why? See Contact & Hours That same page gives our hours of operation.

Back to Top

Copyright © 2008 - 2021 S. G. Botsford

Sherwood's Forests is located about 75 km southwest of Edmonton, Alberta. Please refer to the map on our Contact page for directions.